Art education that blends different forms and architectures helps learners learn about various kinds of art. In the following case study about the Terracotta Temples of Bishnupur, students can learn about the local culture, check out the materials used in building the temples, and understand the social and political background of the temple culture.

Bishnupur, a town in the Bankura district in West Bengal, is well-known for its terracotta temples. The temple walls are extensively embellished with carved and moulded terracotta (baked clay) decorations made from the locally available laterite clay. Similar to the contouring of Vrindavan that had been carried out in the sixteenth century by Chaitanya and the Gaudiya Vaishnava devotees, temples burgeoned in Bishnupur, constructed to establish the ritual worship of images. The deities installed in these temples were named after the icons worshipped and enshrined previously at Vrindavan, notable examples being Madan Mohan, Shyam Raya, Radha Raman, Keshto Raya, Madan Gopal, Murali Mohan, Gopinath, and so forth.

Bishnupur was the capital of the kings of the Malla dynasty, who ruled over the region known as Mallabhum, covering modern-day Bankura, Onda, Bishnupur, Kotulpur, and Indas, till the first half of the twentieth century. However, It was in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during the reign of Hambir Malla Dev, also known as Bir Hambir, the 49th king of the Malla dynasty that Bishnupur began to draw interest from its neighbouring territories, both politically and culturally.

The history of Bishnupur as a religious and cultural hub with its distinctive temple architecture is tied to the Gaudiya Vaishnava bhakti movement, dating back to the sixteenth century in eastern India— Bengal in particular (then known as Gaud or Gaur). The bhakti saint and social reformer, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1533), founded Gaudiya Vaishnavism, a brand of spiritualism marked by an emotive and intimate devotion to the Hindu god Krishna, the central deity of the tradition. Vrindavan—the mythical site where Krishna spent his youth, believed to be located in the woods by the river Yamuna in north India—held a profound fascination for devotees of the Vaishnava faith. Dr. Pika Ghosh opines that Bishnupur’s emergence as an important centre for Gaudiya Vaishnava is tied to the transformation of the forests of Bishnupur into a hallowed centre in an attempt to recreate a ‘Gupta [hidden] Vrindavan’, in Bishnupur (Ghosh 2002).

The narrative, recovered from various Gaudiya Vaishnava texts, draws attention to Bishnupur’s political patronage of the Gaudiya Vaishnava faith,

which helped the order flourish in this region and establish a seat of culture and religion based on the Vaishnava tradition. This alliance with the political authorities of Bishnupur meant that Gaudiya Vaishnavism would have a powerful influence on the distinctive styles of art, craftsmanship, and temple artistry that was on the verge of surfacing in the region. The consequent proliferation of temples in this region over the next century and a half, which British site surveys and administrative reports of the mid-eighteenth century estimate to be between 150 and 450 in number, is probably what gave Bishnupur its reputation as a religious centre (Ghosh 2002).

The temples in which these deities were installed, however, are distinctively atypical. Rather than turning to the architectural styles of Vrindavan for inspiration, they followed local architectural traditions and innovated on their own. These temples were conspicuously distinct from the Vrindavan temples—they were constructed on a new ratna style, reoriented to face south, departing from the nāgara custom of north India and the rekhā style of facing east in the direction of the rising sun (Ghosh 2005). They had two storeys instead of one, with an additional shrine stacked over the conventional sanctum on the lower level. The shrine in the upper pavilion was reserved for special occasions such as festivals, leaving the lower sanctum available for daily worship. One altar was constructed on the traditional east-facing style of Hindu temples, and this deity would be ministered to by the priests of the temple. The other altar, which eventually came to hold greater importance, faced south towards the courtyard and nātmandir (entertainment hall), where devotees would gather to sing praises to Krishna and his heroics, and often spontaneously rise in dance during the ārati. This new temple form served the various ritual needs of the emerging Gaudiya Vaishnava community in Bengal.

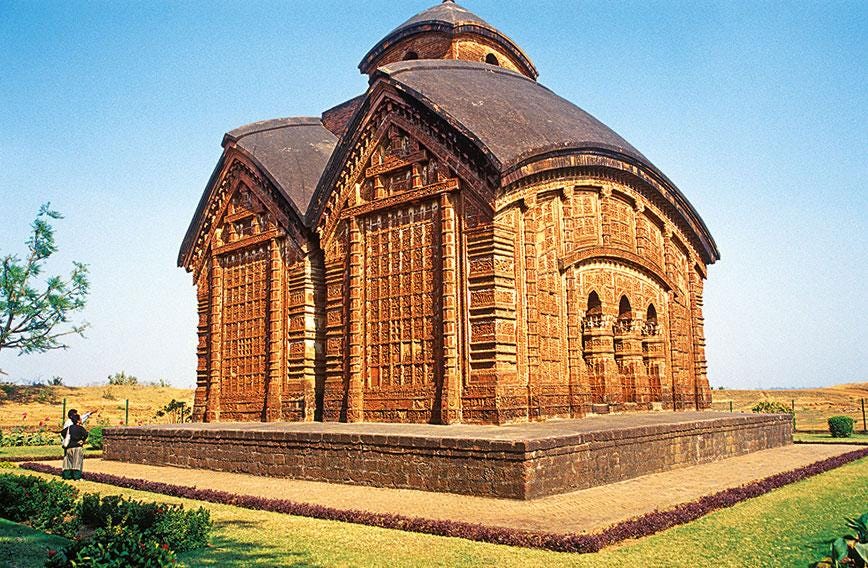

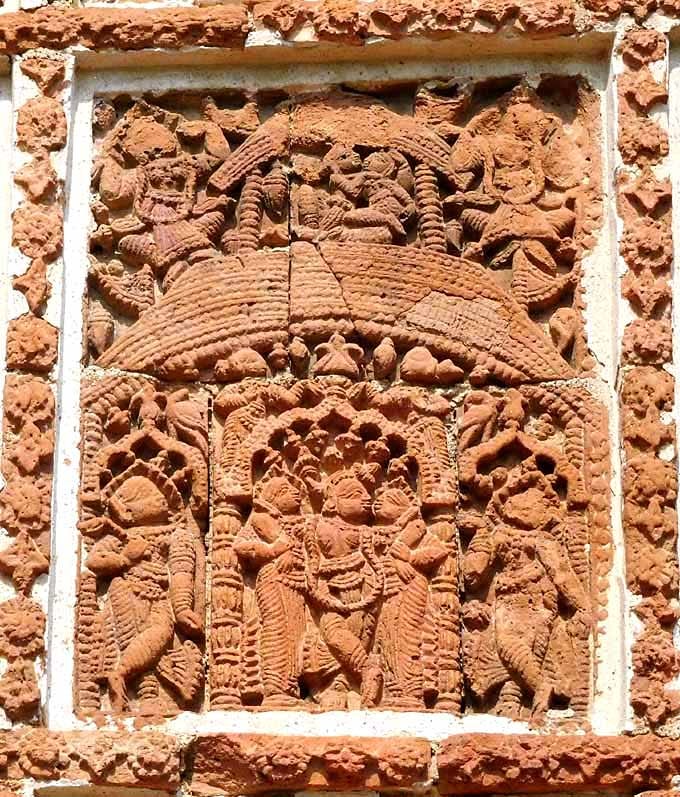

The terracotta work on the Shyam Raya temple (1643), one of the oldest terracotta temples in Bishnupur, is a fine example of the depiction of the rāslilā. This temple was constructed in the pancha-ratna style and is the most richly decorated of all the terracotta temples to be found in the region—every inch of the temple from the interiors to the archway and from the vaulting inside to the towers on the roof are sheathed with fine terracotta work. There are innumerable small plaques embellished with images based on themes such as Krishna embracing Radha or playing his flute to her, Krishna’s battle with Indra for the parijat tree, and Krishna between two gopis under an elaborate canopy. These images are bordered by a profusion of small rhythmic figures and floral and vegetal motifs. Above the archways are panoramic battle scenes depicting gods, demons, warriors, and heroes. Scenes from Puranic legends, the Ramayana, and Krishnalila adorn the rows below, and the plaques at the very bottom depict more contemporary scenes of the raja going to battle or proceeding in his palanquin.

Even though scenes from Krishna’s life were most commonly sculpted on the terracotta plaques, there are also depictions of scenes from other Vaishnava texts and the larger body of the Vishnupurana, as well as legends of other gods and goddesses. For example, the terracotta on the nearby Keshto Raya temple, also famously known as the Jor Bangla temple, built only 12 years after the Shyam Raya temple and with the patronage of the same raja, is just as lavish as its predecessor. The subject matter is also largely similar, but the layout is more intrepid and systematic. The different rows of illustrations depict a single, linear narrative each, with entire rows being taken up by chronological depictions of Krishna’s life from the nursing of Krishna and Balaram to Krishna and Balaram fighting the King’s wrestlers in Mathura, warriors confronting each other on chariots in the battle of Kurukshetra highlighting evocative scenes like Bhishma lying on a bed of arrows, scenes from the Ramlila, and so forth.

Apart from its temple architecture, Bishnupur is also well-known for the craftsmanship of its terracotta figurines, pottery, jewellery, Bengal miniature paintings and other decorative artefacts.

The emergence of Bishnupur as a cultural and religious hub is closely tied to the Gaudiya Vaishnava bhakti movement of the sixteenth century in eastern India. The town played a pivotal role in the flourishing of Gaudiya Vaishnavism due to its political patronage. Bishnupur's artistic legacy extends to various art forms, emphasising the town's enduring cultural and artistic significance in terracotta art, pottery, and other decorative arts. The above case study brings the historical significance of Bishnupur to the forefront. The architectural innovation, craftsmanship, and cultural legacy are notably highlighted.